Unveiling the Past: A Scholar’s Legacy in the Study of Early Judaism

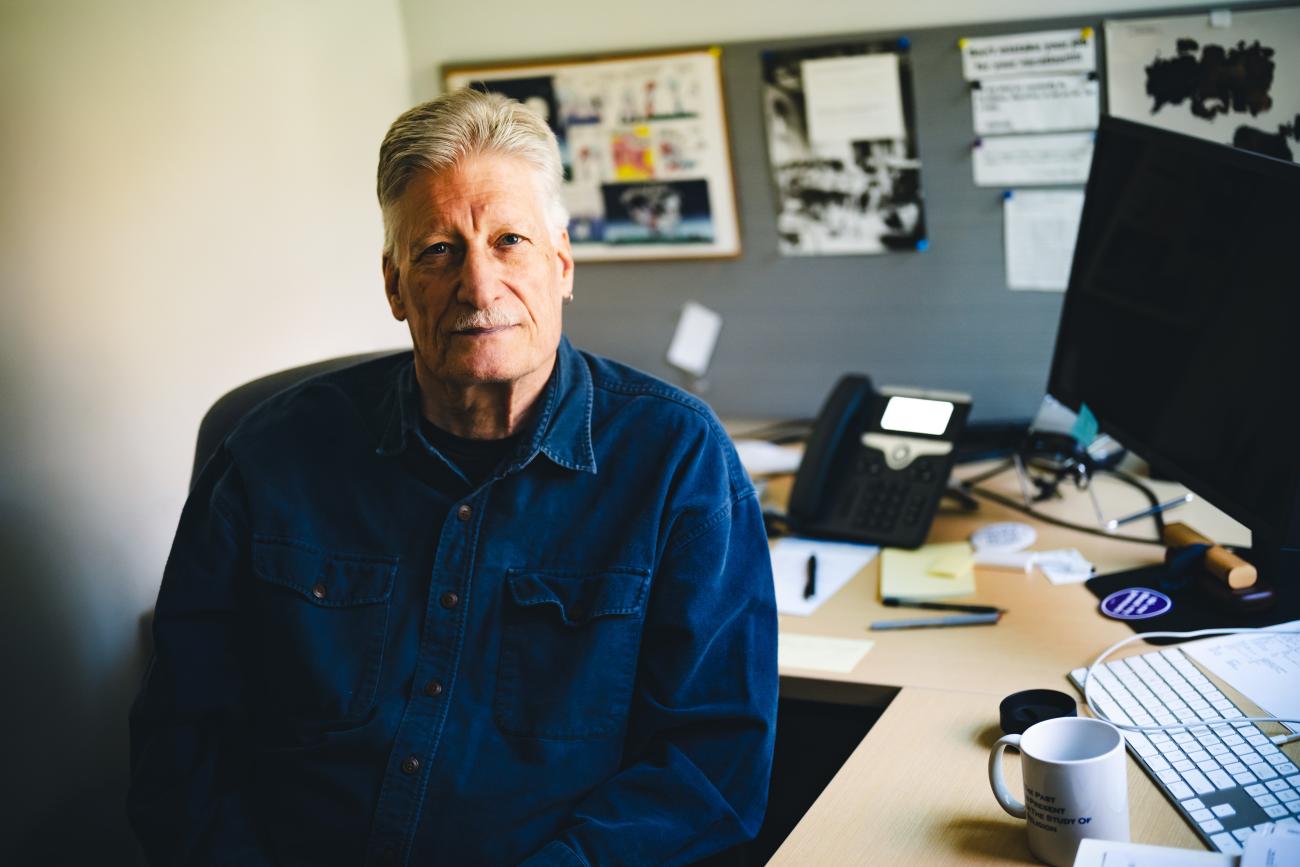

As Ben Wright approaches retirement, the renowned scholar celebrates a career unraveling the mysteries of the Second Temple period and advancing fresh perspectives in early Judaism studies.

Ben Wright has focused his decades of assiduous scholarship on an eventful and sometimes obscure segment of Jewish history known as the Second Temple period (c. 300 BCE–70 CE). It is a slice of the past shrouded by both time and the strange provenances of the many documents historians rely on in their work, understanding, and reconstructing to the degree possible, what has come before us.

A leading expert in the field, Wright has a gift for opening the curtains on history in a way that illuminates the richness and complexity of the issues of the moment, and the way the lives of those who lived in these societies differ from—and in some surprising ways resemble—our own.

Wright, University Distinguished Professor at Lehigh and professor of religion, culture, and society will retire at the end of 2025, and he has organized a valedictory conference titled “Studying Early Judaism in the 21st Century,” set for March 24-26 at Lehigh. “It seemed like a good time to take stock of what we have done in the first quarter of this century,” he says The conference is being organized in conjunction with the Philip and Muriel Berman Center for Jewish Studies, which is celebrating its 40th anniversary.

“I've been involved in the Berman Center since I came to Lehigh in 1990, and I’m delighted to be a part of this 40th anniversary year,” Wright says. “It's a big milestone for the program, and I'm really looking forward to the conference. The lineup of people coming in and presenting is really impressive.”

Over the course of Wright’s illustrious, four-decade career, he has written or edited seven books, published more than 200 scholarly papers and articles, and won awards and recognitions too numerous to list here. His work on the Second Temple period—a time which ends with the siege of Jerusalem by the Roman general Titus—was also the period of the development of the Hebrew Bible.

“There are no collections of texts at that time that all ancient Jews agreed upon which would be the equivalent of the Bible,” says Wright. “People had texts that they thought were really important, some of which ended up in the Jewish Bible, but others didn’t.”

It was also a tremendously dynamic era, an era in which, Wright explains, Jews could and did explore and express a wide variety of ideas. “This is a very fertile period of thought. Jews lived across the ancient Mediterranean and all the way to the East, and Roman Jews were as different from Alexandrian Jews or Jerusalem Jews as Lithuanian Jews might be from South Jersey Jews today.”

Wright says the study of early Judaism has changed since he entered the field in the 1980s. For that reason, he went out of his way to invite a significant group of younger and mid-career scholars to the upcoming conference to explore new aspects of the research being done. “How has our approach to studying early Judaism changed," he asks, "and what kinds of questions are we asking now that we weren't asking before?”

One answer, says Wright, is that scholars of religion are casting a wider net in their inquiries. “I started my doctoral program in 1978. We worked with what in my area is called the historical-critical method, which was the standard in the field for a long time,” Wright says. “The younger scholars, many of whom are now friends, are working in a different way from the way I worked in the 80s and using methods from different areas. I get pushed by my younger colleagues on these kinds of questions, and it's really healthy and good.”

Now, Wright often finds himself delving into literary criticism or taking on anthropological or sociological questions in his work. “In the 80s, for instance, we weren't asking questions about how ancient peoples constructed their identities. We ask those questions now.”

As an example, Wright brings up the Letter of Aristeas, a second century BCE Jewish text from Egypt that relates the story of the oldest translation of the Hebrew Pentateuch, or Torah, into Greek. “We talk a lot in our field about what we call Hellenistic Judaism. It could have a notational hyphen in it, similar to Italian-American,” Wright says. “Did the author of this letter consider himself a kind of Greek-ized Jew? I don’t think so. If we had the author of the Letter of Aristeas in front of us and asked if he were a Hellenized Jew, I don't think he’d know what that meant. He’d say he was both!”

Wright says this hypothetical dialogue shows that even more than 2,000 years ago, static representations of identity blur the complexity of social realities. “We've learned that identities are fungible. They develop, they change, and they're different in different contexts,” says Wright.

Another aspect of Wright’s research that presents deep complexity is the fragmentary nature of the historical documents he studies, and a different outlook on the sanctity of original texts in the past. He gives the example of chapter two of Genesis. “The Hebrew says, ‘On the seventh day God finished the work that he had done and on the seventh day, he rested from all the work that he had done.’ Of course, the Jewish Sabbath is a day which is supposed to be for rest, so the text is a little weird,” Wright says. “It suggests that God might have worked on the seventh day. He got up in the morning, trimmed the hedges, edged the grass, did the last few little details, and then he finished by noon and went off and watched college football or something.”

When you get to the Greek translation, there is a change. “It reads, ‘On the sixth day God finished the work that he had done, and on the seventh day’ God rested. Somewhere along the line, whether it's in Hebrew or Greek—we really don't know—somebody noticed the problem,” Wright says. “No one in the modern world would think of changing the text. But we have one version that suggests that God worked on the seventh day, and one that says God finished on the sixth day, which resolves the problem completely. So, there's a different attitude toward the text in antiquity from the one we have when we talk about Bible.”

This kind of thing this is commonplace in the study of ancient Judaism, Wright says, in part at least because, at that time, the texts were still developing. “Take the book of Jeremiah from the Hebrew Bible. There are at least two or three different versions among the Dead Sea Scrolls. They're very different, and they exist side by side. It suggests that people knew the differences, used them side by side, and didn't have any problem with that,” he explains. “I'm teaching my course in early Judaism this semester to go along with the conference, and it’s one of the first things I’ll talk to the students about. They're going to come into the classroom with this idea that texts are fixed, and it’s simply not the case.”

Since the 1980s, Wright has been working on a text called the Wisdom of Ben Sira and is currently writing a commentary on that book with a French colleague. The text is an important example of a wisdom book from the period, instructions on how to live a life. The book of Ben Sira, says Wright, is kind of a training manual for young men who wish to be part of the bureaucracy. “Some of it is career advice. My favorite is the part that says, if you're at a banquet and you're going to throw up, make sure you go outside. Then as now, that’s pretty good advice,” he says. The book also covers philosophical and theological topics. "So, the career advice and these very complex existential questions are all in the same book.”

The Wisdom of Ben Sira is also a case study in the kinds of vexations those who study the period have dealt with regularly as an occupational hazard. The book was originally written in Hebrew and translated into Greek by a person who called himself the original author's grandson. The Hebrew version did not survive fully intact. “Currently, about 70 percent of the book exists in some form of Hebrew, most of it in manuscripts that date up to 1,400 years after the book was written. Whenever you work with this book, you really need to be working with Greek, Hebrew, Latin and Syriac,” Wright says. “I’ve been working through textual notes and translation, and I’m on chapter 17. There are 51 chapters. I’m hoping to finish before I’m dead.”