Through the Eyes of Franz Kafka

The latest book by Nicholas Sawicki delves into the iconic author’s interest in the visual arts

The German-speaking Jewish author Franz Kafka is considered by many to be one of the great 20th century writers. His prominence is so significant that we sometimes even use his name as an adjective. His work has influenced many 20th century writers and has been the focus of many literary scholars. Perhaps less well known is that Kafka was also a prolific artist, and on the 100th anniversary of his death last year, his sketches, drawings, and interest in modern art are the subject of a new book co-edited by art historian Nicholas Sawicki.

Co-edited with Marie Rakušanová, an art historian at Charles University in Prague, Through the Eyes of Franz Kafka: Between Image and Language follows Kafka’s interest in art and explores the variety of images that surrounded Kafka in his home city of Prague, as well as the drawings that Kafka produced in his lifetime. The book accompanies an exhibition that opened in June and was curated by Rakušanová.

“My colleague, Marie, invited me a couple of years ago to work with her on this monograph, which is paired with an exhibition that she curated at the Gallery of West Bohemia in west Bohemia.” Sawicki says. “The premise of the exhibition and the monograph is to dig into Kafka's relationship with visuality and with visual culture, both as a consumer and producer of images. That's a topic that hasn't yet been extensively explored in scholarship and it's something that both she and I have been thinking about deeply for the last decade or so.”

Joining Sawicki and Rakušanová, are contributing essayists Miroslav Haľák and Alexander Klee, art historians at the Belvedere Museum in Vienna, and Marek Nekula, professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Regensburg. The book maps how Kafka engaged with local painting and sculpture, architecture, and monuments found across Prague, and with an array of popular visual media and phenomena ranging from illustrated magazines and advertising to film, photography, dance, and cabaret, and it examines Kafka’s own artistic production.

Kafka’s attention to the modern visual culture of his era was reflected in his writings and in his interest in drawing, a practice in which he received preliminary training and which he took up in his free time during his years as a university student. Through the Eyes of Franz Kafka: Between Image and Language is the first book to comprehensively examine his connection with visual art and culture across a range of media, and to address his connections to the artistic scene in Prague in the early 20th century. There was a particular interest for Sawicki, whose major research area is early-20th-century central and eastern European modernism. The author of four books, he writes on modern art in Prague and Czech art, as well as on the history of exhibitions, collecting, and transnational artistic exchange. Through the Eyes of Franz Kafka is the first book to comprehensively examine his connection with visual art and culture across a range of media, and to address his connections to the artistic scene in Prague in the early 20th century. There was a particular interest for Sawicki, whose major research area is early-20th-century central and eastern European modernism. His research focuses on overlooked histories of modernism, to expand and in some cases challenge conventional scholarly narratives in the subject area.

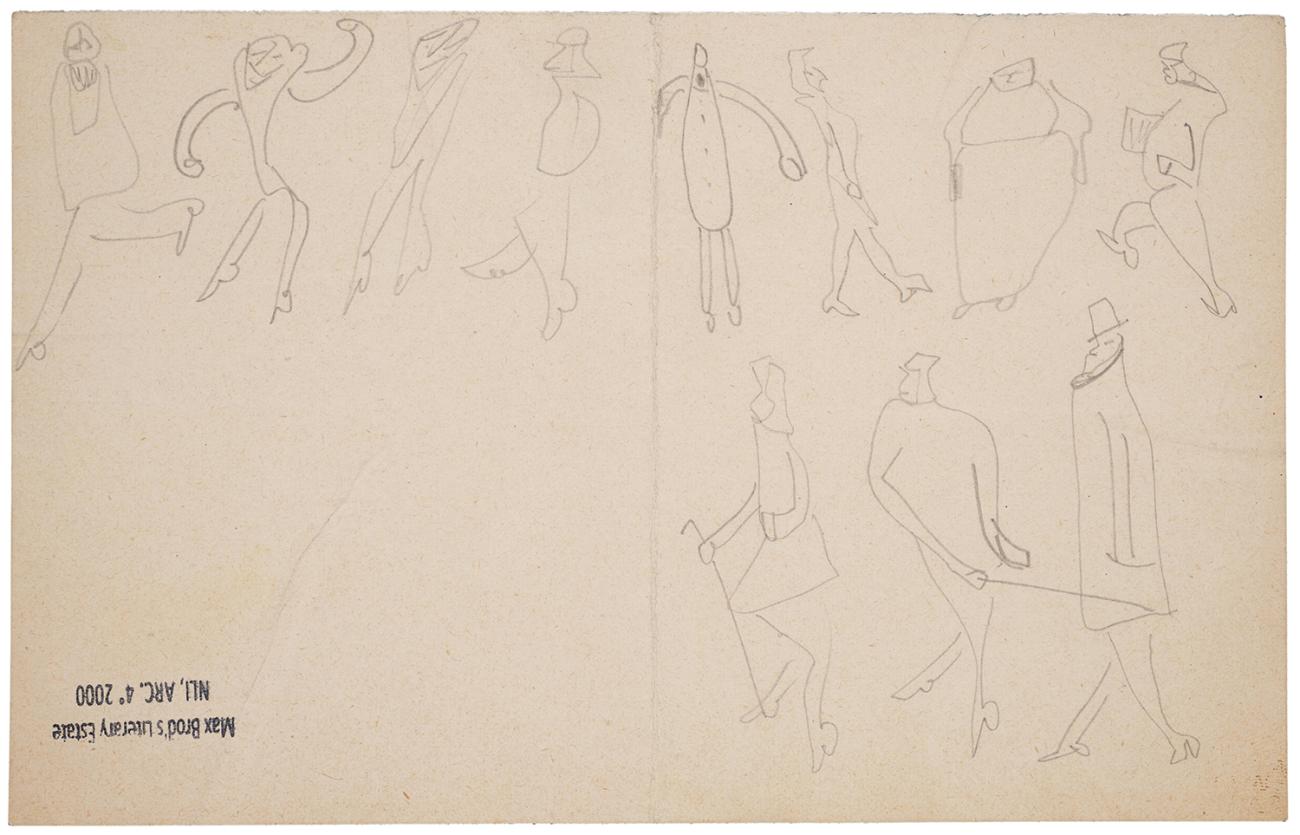

“My interest in Kafka began with an interest in his drawings, which were rediscovered through an Israeli Supreme Court case in 2016 that ruled the transfer of previously unpublished materials formerly owned by Max Brod from a safe deposit box in a bank in Zurich to the National Library of Israel. And when the contents of that vault in Zurich were opened, the scholars and officials who were invited to take part in that process discovered that the vault was among other things full of drawings by Kafka. We had until that point known that Kafka had an interest in drawing, but we had seen very few of his drawings. The first of them were reproduced in the 1937 biography that Max Brod published in Prague, but beyond that very little was known.”

Kafka trained as a lawyer, and after completing his education was employed by an insurance company, yet he spent most of his free time writing. Brod kept Kafka’s drawings after the writer died in 1924, taking them with him when he fled the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia for Palestine in 1939. Later, Brod moved part of his archive of Kafka’s papers for safekeeping to Zurich and bequeathed the drawings to his secretary Ilse Esther Hoffe. After Hoffe died in 2007, the National Library of Israel sued her heirs for the collection. The legal battle took about a decade. Ultimately, the library won its claim.

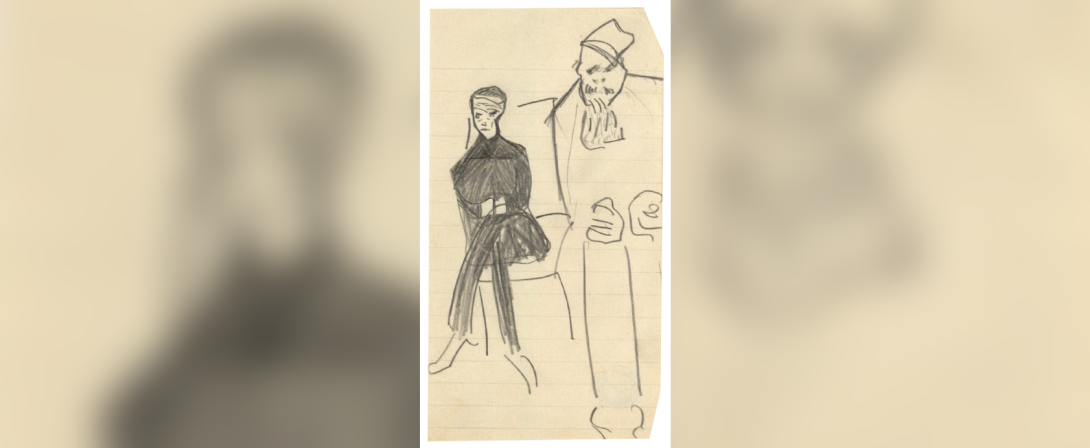

The book and Sawicki’s contribution draw heavily on archival and visual sources to illuminate the connections and context within which Kafka was working and his personal relationships with artists, which were very significant. While studying at Charles University from 1901 to 1906, Kafka took private drawing classes and attended art history lectures. This period and the few years thereafter were the most prolific for his drawings. Kafka’s main interest as an artist was people and the human body, Sawicki says.

“In the drawings that were rediscovered in Zurich we see a large majority focused on people,” he says. “Some of them are relatively naturalistic, where Kafka focuses tightly on the face or some aspect of the body and really develops it in a fairly conventional way. These are quickly rendered, but they carry a lot of the traditional techniques of drawing, such as shading and modeling and line.

“Then we also have a whole range of drawings also focusing on people where he zooms out and takes in the whole of the body. In those drawings, we start to lose detail. In place of detail, we see Kafka really elaborating on the gesture and the movements and comportment of the body and sometimes exaggerating those movements in ways that amplify them. The movement of the body, the way people carried themselves was very interesting to him.”

In a profession where scholarly work is often conducted individually in locations like archives, libraries and museums, this monograph was a welcome project due to its cooperative process, Sawicki says.

“I've become more and more interested as time has gone on in collaborative work. The thrill and the excitement of this project for me was working with a close colleague in the Czech Republic and three other truly phenomenal scholars on a project in which we were all learning together from one another. I also consulted on and provided research for the exhibition that the monograph accompanies. That kind of collaboration is exciting, and to work on a major literary figure such as Kafka and show what art history can add to our understanding of his work is incredibly rewarding.”