From Substances to Processes: Rethinking Minds, Norms, and Reality

Mark Bickhard proposes a new metaphysical model in his latest book, The Whole Person

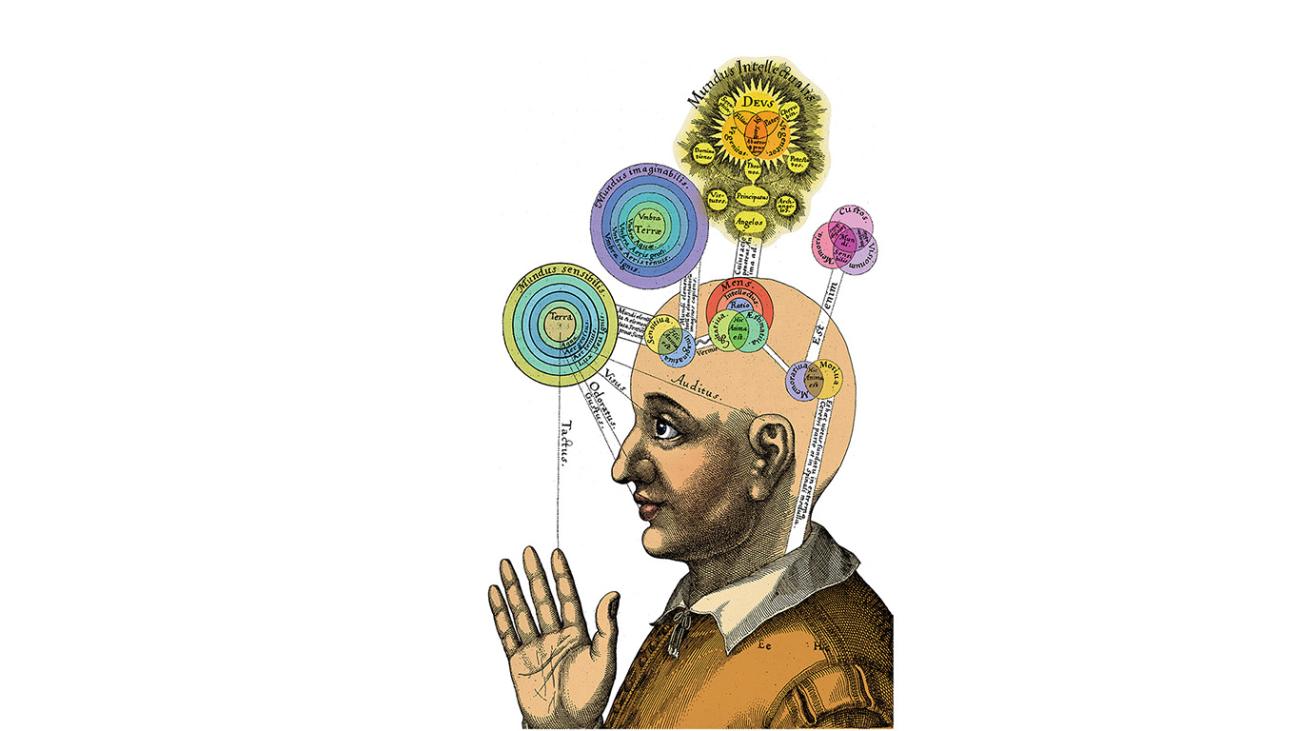

The history of science is a story of how humans see the world and the continual reassessment of our assumptions about our place in it. There has been a metaphysical divide for centuries between the natural world and the domain of the mind. Theoretical psychologist Mark Bickhard argues that there are essential relationships between the two. His latest book presents a model to understand how minds emerge from, yet remain connected with, the world of facts. He proposes a new model of metaphysics that shifts this understanding from a framework of substance to one of process that enables an integrated account of the appearance of normative phenomena.

Bickhard, who holds appointments in the departments of philosophy and psychology, explores the spaces of theory and philosophy concerning minds and persons. His book, The Whole Person: Toward a Naturalism of Minds and Persons, focuses on the evolutionary and developmental occurrence of normative phenomena out of prior forms of process and proposes models of, among other phenomena, biological function, representation, and other cognitive issues.

“Fundamentally, there's substances—atoms, facts, causal relations, etc., and then there's intentionality, normativity, and there's a split that goes all the way back to the Greeks,” says Bickhard, Henry R. Luce Professor of Cognitive Robotics and the Philosophy of Knowledge. “People have attempted to try to deal with it in some way or another. There's matter and form, for Aristotle. There are two different kinds of substance, for Descartes, a famous predecessor. You can try to go just with one. You can say, "Well, everything is just atoms," like Hobbes. Or you can say, "Well, everything is really just mind, and you arrive at idealism. But the dominant idea, for most of the 20th century, has been, everything is just particles, facts, and causes. But nobody's ever been able to make good on that.”

Bickhard presents a new paradigm, a process metaphysics. This process model of representation, called interactivism, requires changes in many related disciplines. His arguments pay particular attention to three domains in which changes are induced by the representational model: perception, learning, and language. This interactivist model of representation and cognition is an action and interaction-based approach, he says. It involves fundamentally different assumptions about representation than generally accepted models and presents a fundamentally different metaphysical framework from the substance, structure, and particle frameworks that are still dominant in most of philosophy, cognitive science, and psychology. He focuses on the evolutionary and developmental emergence of normative phenomena out of prior forms of process.

“Aristotle, historically, has been the primary source for matter-informed ways of thinking about things, and therefore, for substance ways of thinking about things,“ he says. “If you want to think about substance, most people will think Aristotle. Aristotle has been the primary source for matter-and-form ways of thinking about things. What I’m arguing for is a process metaphysics. And process metaphysics has been on the table since Heraclitus, who pre-dates Parmenides and Aristotle and so on, who are some of the primary proponents of matter and substance frameworks. (My model) isn’t reinventing entirely, but it is saying, ‘Look, we really need to do this right. And in order to do it right, we've got to use a process model. And here's a way of thinking about process metaphysics.’ I don't, in a certain sense, propose full process metaphysics. It seems to me that that ends up being physics. And we already have process models in physics. They're called quantum field theories.”

The Whole Person presents an integration of decades of work, an exploration into the foundational role of mental processes in the emergence of social realities and persons, with language acting as a core element in these emergences. The compelling force behind Bickhard’s work comes from philosophical and psychological perspectives—how can we represent the world? Part of his research applies to work in cognitive science. He focuses primarily on normative biological function, representation, and cognitive issues in an effort to demonstrate how different types of phenomena of the mind are realized in its processes. This requires an account of how normative mental phenomena are emergent in underlying biochemical processes. Addressing evolutionary aspects, brain processes, developmental processes, moral normativities, and self-consistency considerations, Bickhard posits that issues of representation permeate everywhere in psychological and social phenomena — perception, memory, motivation, learning, emotions, consciousness, language, social ontology, and others.

There are good reasons to abandon substance and particle metaphysical frameworks, and to explore process frameworks, Bickhard argues. These frameworks include interactive models of representation and cognition, rather than strict information-processing models. Substance and encoding presuppositions have permeated Western thought for millennia, and attaining a fresh process and interactive view is not easy, he says, but accepted frameworks no longer work conceptually and empirically, and it is time for the process alternative to emerge.