Reimagining the Round Table: Restoring Medievalisms of Contemporary Women Writers

Suzanne Edwards' edited volume with Matthew X. Vernon highlights women's medievalism which has often been silenced

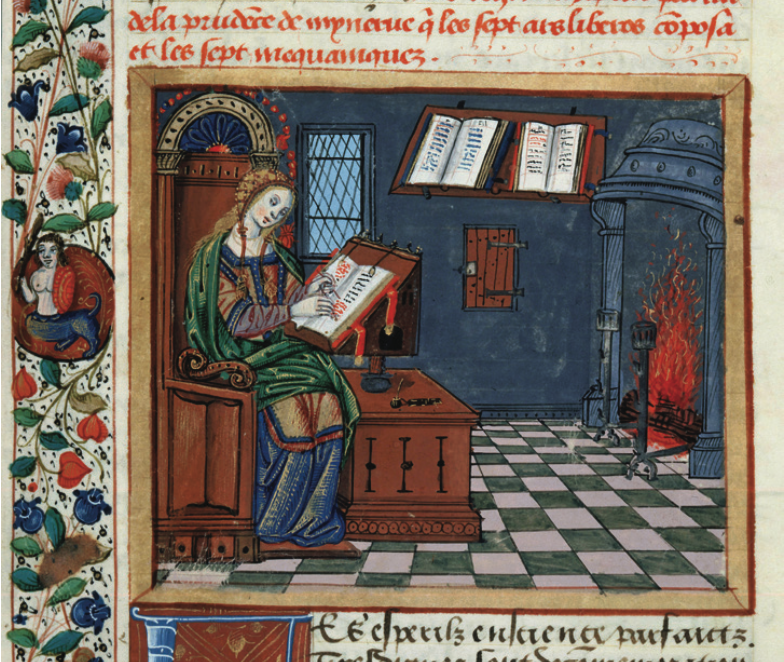

When imagining the Middle Ages, jousting arenas, turkey legs, and knights in shining armor often come to mind. However, this masculine, Westernized view of the medieval period excludes a wealth of diverse narratives and perspectives. Suzanne Edwards is changing that with a volume of essays on women’s medievalism that she’s co-editing with Matthew X. Vernon.

“Medievalism includes representations of the Middle Ages in any moment after the Middle Ages from Spenser’s sixteenth-century The Faerie Queene to the movie Camelot or even Games of Thrones,” Edwards, professor of English, explains, naming a few popular examples. Historically, scholarship on medievalism has often focused on the works of white male authors like Tennyson, T.H. White, and Tolkien.

“In attending to the history of medievalism, we’ve largely overlooked the contributions of women writers in particular,” Edwards says. “What we found in writing the book is often those contributions by women writers have not been recognized as medievalism or they have remained hidden in the archive.”

In ten essays and an introduction, Women’s Restorative Medievalisms: Forgotten Pasts and Unimagined Futures sheds light on these unrecognized medievalisms by women writers from the 20- and 21st-centuries.

“Women writers in their medievalisms call attention to histories of oppression as well as imagine alternative possibilities for the past that might lead us toward a different kind of future,” Edwards notes.

For instance, Tracy Deonn’s young adult novel Legendborn is a popular contemporary example that Edwards and Vernon, professor of English at the University of California-Davis, discuss in their introduction. Featuring an African American teenage girl as Arthur’s heir, “[Legendborn] lays bare the intimacies between Arthurian legend and racially gendered histories of enslavement in the United States, gesturing toward new possibilities for social coalition.”

The first section of essays grapple with canonical European literary works through the lenses of race, language, and place. The second section broadens the scope beyond Europe, while the third section addresses what historically has been silenced, reproducing historical absences. The final section bridges the gap between academic and creative writing.

“The history of medievalism obscures the significant contributions of women writers.”

When Edwards and Vernon reached out to scholars to contribute to the volume, the response was enthusiastic: “Almost everyone we reached out to agreed to contribute.” This enthusiasm underscores the need for the intersectional feminist framework the book provides.

Edwards and Vernon first connected over their love of the work of Gloria Naylor and her creative engagements with medieval literature. “Working with Matthew has been a dream,” Edwards says. Together with Mary Foltz, associate professor of English at Lehigh, Edwards co-directs the Gloria Naylor Archive project, which makes the author’s collected papers more accessible to scholars, teachers, students, and fans.

Edwards’ passion to highlight women’s medievalisms has only grown, and she is planning a monograph on the subject.

The portrayal of the Middle Ages by women is one that centers “community and resistance across geopolitical boundaries,” Edwards explains. This shift allows us to imagine a different kind of Middle Ages—one where the story might not revolve around 12 white knights sitting at King Arthur’s round table.